Why Mean-Variance Optimization Breaks Down

And how to make it actually work

Introduction

Mean–Variance Optimization (MVO) is a central framework for portfolio construction: choose weights that balance expected return against risk as measured by variance.

In its classical form, MVO is elegant, convex (under mild conditions), and analytically tractable. Yet practitioners quickly encounter a paradox: the mathematically “optimal” portfolio built from estimated inputs is often unstable, highly leveraged (explicitly or implicitly), and disappoints out-of-sample.

This is not a minor implementation detail; it is a structural consequence of combining a high-dimensional optimizer with noisy estimates of expected returns and covariances.

This article develops MVO from first principles and then explains, in a mathematically explicit way, why raw MVO tends to maximize estimation error.

Finally, it surveys the spectrum of practical fixes, organized around two levers: (i) improving or regularizing the inputs (expected returns and covariances), and (ii) constraining or regularizing the optimizer (the feasible set and the objective).

The unifying theme is that almost every successful “fix” works by injecting bias in exchange for a large reduction in variance of the resulting portfolio weights, thereby improving out-of-sample performance and implementability.

The Classical Framework

Notation

Consider N risky assets. Let the random vector of (excess) returns over a single period be

Define the (unknown) population mean and covariance

A portfolio is a weight vector interpreted as a fraction of capital invested in each asset.

The basic budget constraint is

where 1 denotes the all-ones vector in R^N. In other words, the weights should sum up to 1. Additional constraints like no-short, leverage limits, or sector bounds will be presented in the following chapters.

Under this setup, the portfolio return is linear in weights:

The expected portfolio return and variance are

Two foundational facts are worth stating explicitly because they explain why MVO becomes a quadratic program:

1. Expected return is linear in weights. This makes the “reward” side easy to compute but also extremely sensitive to errors in mu, because the optimizer can exploit tiny differences in mu via large weight changes.

2. Variance is quadratic in weights. The covariance matrix Sigma couples assets through correlations: diversification is precisely the exploitation of off-diagonal terms in Sigma. The quadratic form w^T Sigma w is convex in w if Sigma is positive semidefinite, and strictly convex if Sigma is positive definite, which ensures the uniqueness of the minimum-variance solution under typical linear constraints.

The Markowitz Problem in Matrix Form

Markowitz’s original formulation can be stated as: among all portfolios with a given expected return, choose the one with minimum variance. Fix a target expected return m. The constrained optimization is

If short-selling is disallowed, one adds w >= 0 componentwise. If leverage is limited, one might add |w|_1 <= L, where |.| denotes the L1 norm, and so on.

Why is the covariance matrix central here? Because for any two assets i and j,

The diagonal terms w_i^2 Sigma_{ii} represent contributions from each asset’s variance; the off-diagonal terms w_i w_j Sigma_{ij} represent interaction through co-movement. Diversification is not “holding many assets” per se; it is selecting weights so that positive and negative interactions among returns reduce overall variance.

A subtle but important point: variance is a second-moment object. It treats positive and negative deviations symmetrically and is fully described by Sigma. This makes MVO analytically convenient, but it also means the framework inherits all limitations of second-moment risk measures; non-normality, fat tails, and asymmetry are not captured unless the distribution is (approximately) elliptical. In many institutional contexts, however, variance remains a useful proxy because it aligns with tracking error, volatility targets, and risk budgeting infrastructure.

The penalized (risk-aversion) form and its equivalence

An equivalent way to pose the trade-off is to maximize a mean-variance utility function:

where gamma > 0 is the risk-aversion parameter. Larger gamma penalized variance more heavily, shifting the solution toward lower-risk portfolios.

The equivalence between (MVO-1) and (MVO-2) is practically important. The constrained form (MVO-1) traces the efficient frontier by varying m. The penalized form (MVO-2) traces it by varying gamma. In many production systems, gamma is tuned to meet a risk target or tracking error budget.

Solving the classical problem: Lagrangian and closed-form structure

To make mechanics concrete, consider (MVO-2) without additional constraints beyond the budget constraint. Form the Lagrangian

with Lagrange multiplier eta enforcing 1^T w = 1.

First-order optimality (assuming Sigma is positive definite) gives

hence

Imposing the budget constraint 1^T w = 1 yields

so

Substituting (1.2) into (1.1) gives the explicit optimizer.

This expression reveals a key structural fact that will matter later: the optimal weights are built from Sigma^{-1} mu and Sigma^{-1} 1. In other words, the inverse covariance matrix is the central operator transforming expected returns into weights. When Sigma^{-1} is unstable (ill-conditioned or poorly estimated), the entire solution becomes unstable.

For the return-target form (MVO-1), the Lagrangian with multiplies lambda, eta is

The first-order condition is

Define the classical scalars

Assuming Sigma is positive definite and mu is not collinear with 1 under Sigma^{-1}, one has Delta > 0. Solving for lambda, eta yields a closed-form frontier, and the efficient frontier in (sigma^2, m) space is a parabola:

The frontier’s curvature and location are completely determined by (A,B,C), i.e., by Sigma^{-1} and mu. This already hints at the practical challenge: every point on the frontier depends on inverting Sigma and multiplying by mu, precisely the operations most vulnerable to estimation noise.

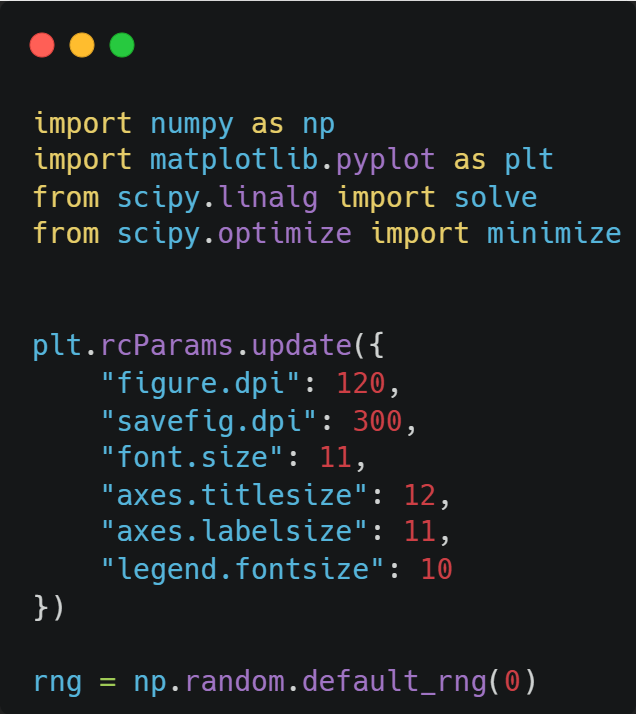

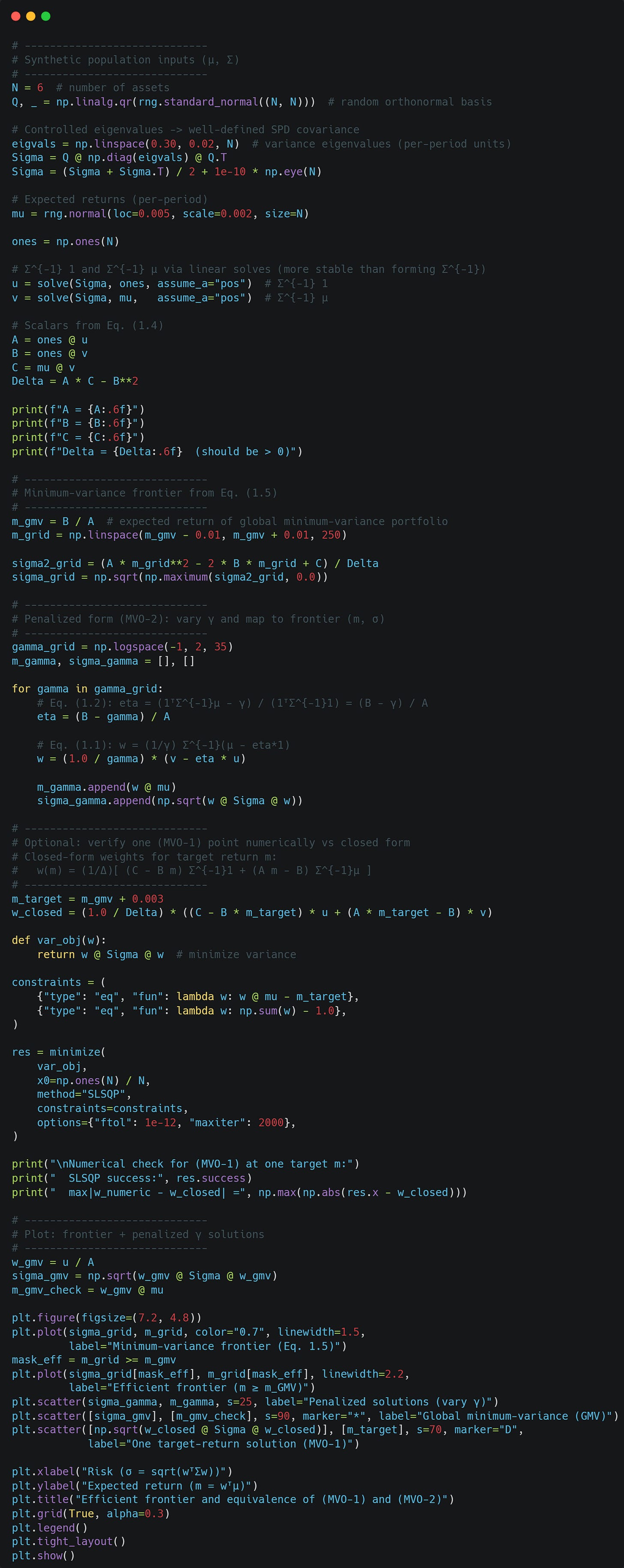

Let’s implement this in Python and look at the resulting efficient frontier. We will also compare our closed-form solution of (MVO-1) to a numerical solution to verify that we did everything right.

As you can see, our closed-form solution and numerical solution are pretty much identical, and the (MVO-2) solutions lie on the efficient frontier traced by the (MVO-1) solution, so they are indeed equivalent.

Interpreting Sigma: Risk Geometry and Diversification

It is useful to interpret the quadratic form geometrically. If Sigma is positive definite, then the set of portfolios with equal variance sigma^2,

is an ellipsoid in weight space. The optimizer in (MVO-2) chooses the point on the budget hyperplane {1^T w = 1} that maximizes a linear functional w^T mu minus a quadratic penalty. The optimum balances moving “up” in the direction of mu while staying within low-risk ellipsoids determined by Sigma.

This picture is clean when mu and Sigma are known. The moment we replace them with estimates, the ellipsoids tilt and stretch unpredictably, and the direction of “up” becomes noisy. The optimizer, being deterministic, will still choose an extreme point, often an extreme point of the wrong geometry. That is the beginning of the “error maximization” story.

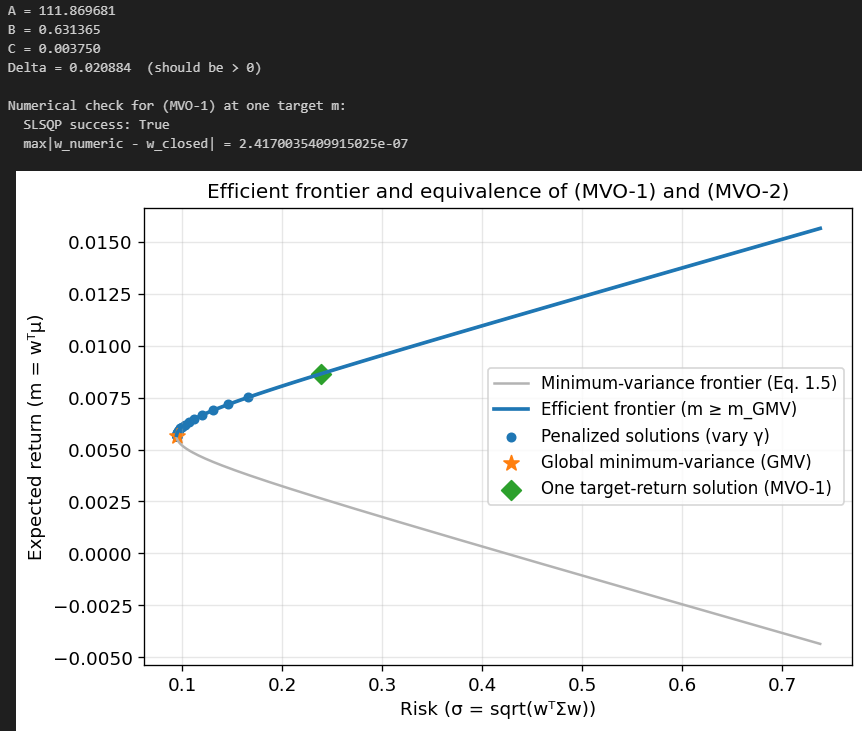

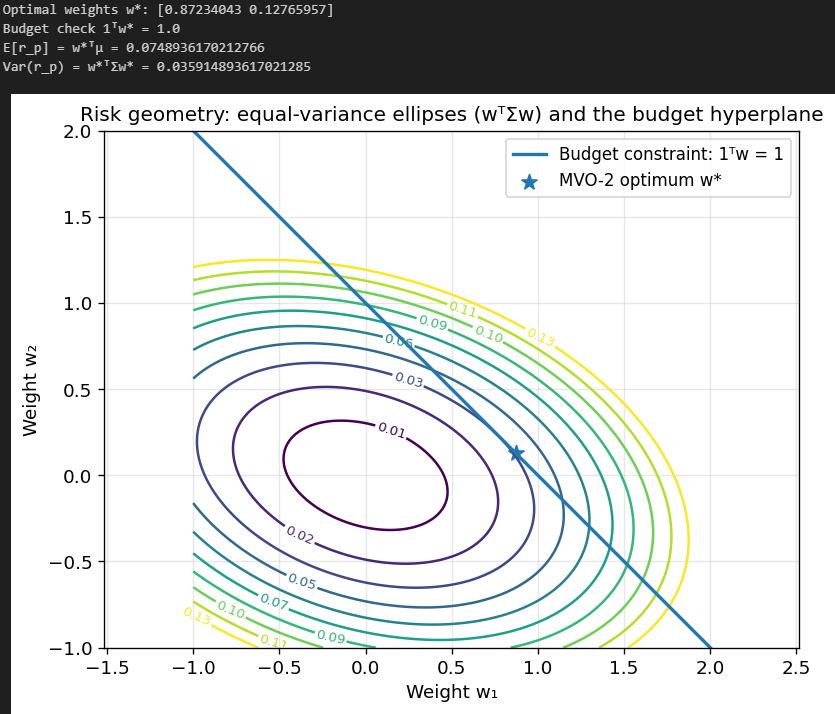

Here is an example using two assets:

Each ellipse here corresponds to portfolios with equal variance. As you can see, our optimal portfolio just barely touches the 0.03 variance ellipsoid, and any other portfolio on the line (that satisfies the budget constraint) results in a higher variance.

The “Error Maximization” Problem

Raw MVO is often described informally as “garbage in, garbage out.” That statement is true, but it understates the severity: MVO does not merely propagate input error; it can amplify it. In high dimensions, the amplification can be dramatic enough that the optimizer effectively learns the noise in the estimated inputs.

This section makes that mechanism explicit.

MVO is not an optimization problem; it is a statistical decision problem

In theory, (mu, Sigma) are population quantities. In practice, we never observe mu or Sigma. We observe a finite time series

and produce estimators hat{mu} and hat{Sigma}. The most common “plug-in” estimators are the sample mean and covariance

Then the raw MVO portfolio is

or its return-target equivalent.

Crucially, hat{w} is a function of the random sample; it is itself random. The “true” objective we actually care about is out-of-sample performance under the true distribution, e.g., maximizing

But plug-in MVO maximizes a different random objective,

The practical question is not “is hat{w} optimal for hat{U}?” (it is, by construction), but “how does U(hat{w}) compare to U(w^\star), where w^\star maximizes U?” That gap is the cost of estimation error and model uncertainty.

Why expected return estimation is the Achilles’ heel

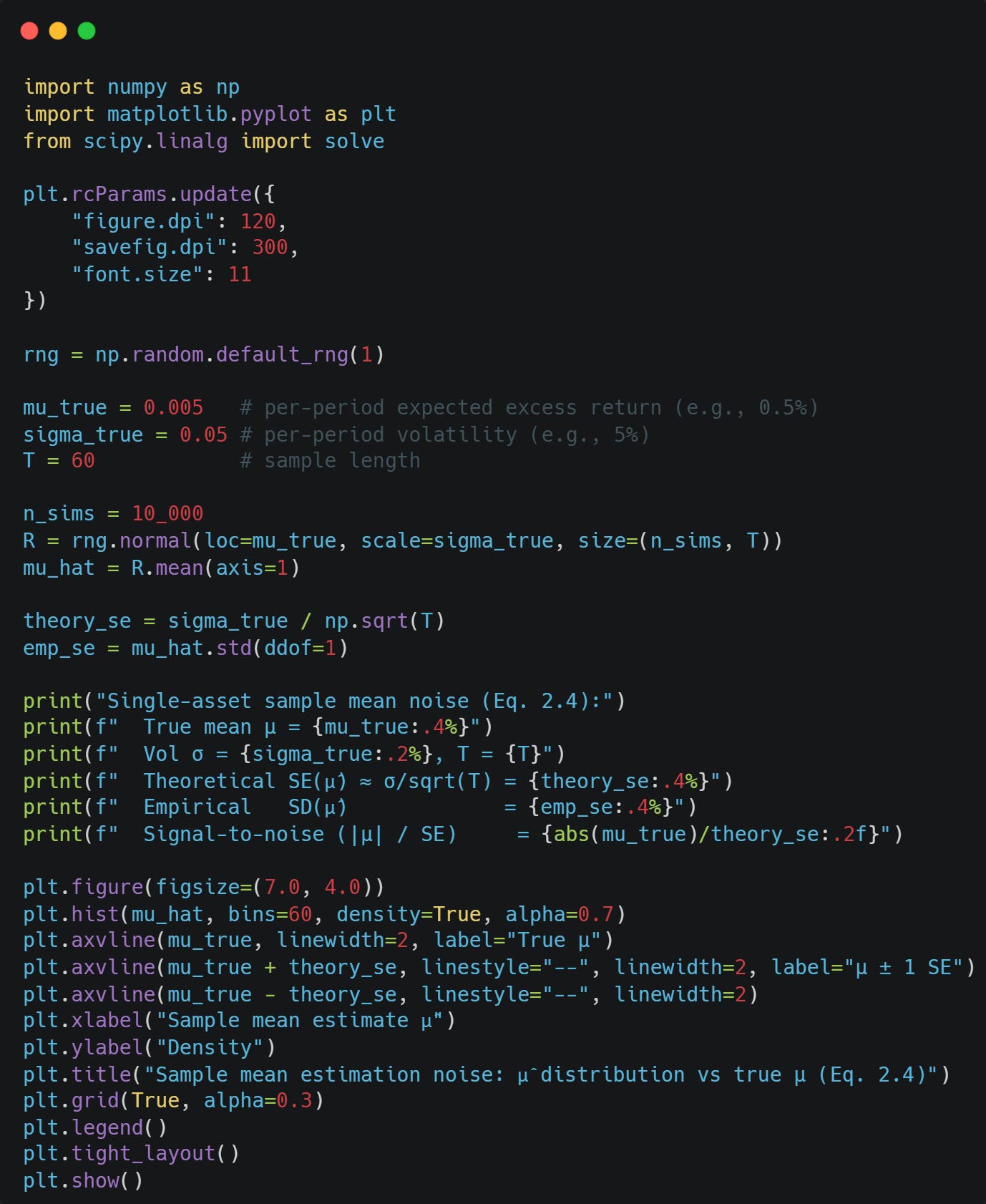

Start with expected returns. For each asset i, the sample mean hat{mu}_i has a standard error on the order of

where

In many liquid asset classes, annualized volatilities might be 10% - 30% while annualized expected excess returns might be 2% - 8%. Translating to a monthly scale, the noise in the sample mean can be comparable to, or larger than, the signal. This is a fundamental signal-to-noise limitation, not an implementation defect.

Now multiply that limitation by dimensionality. MVO compares assets and tries to exploit differences in mu. When mu is noisy, the differences the optimizer sees are often dominated by noise. The optimizer is then rewarded (in-sample) for taking large positions in the assets that happened to have high realized returns in the estimation window, even if that was random luck.

Because the expected return term w^T mu is linear, any error in mu shifts the gradient of the objective directly. In contrast, the covariance term is quadratic and tends to act as a smoothness penalty. This asymmetry is why MVO is particularly fragile to errors in mu.

Here is a simple numerical simulation of how much noise can affect our estimate of mu:

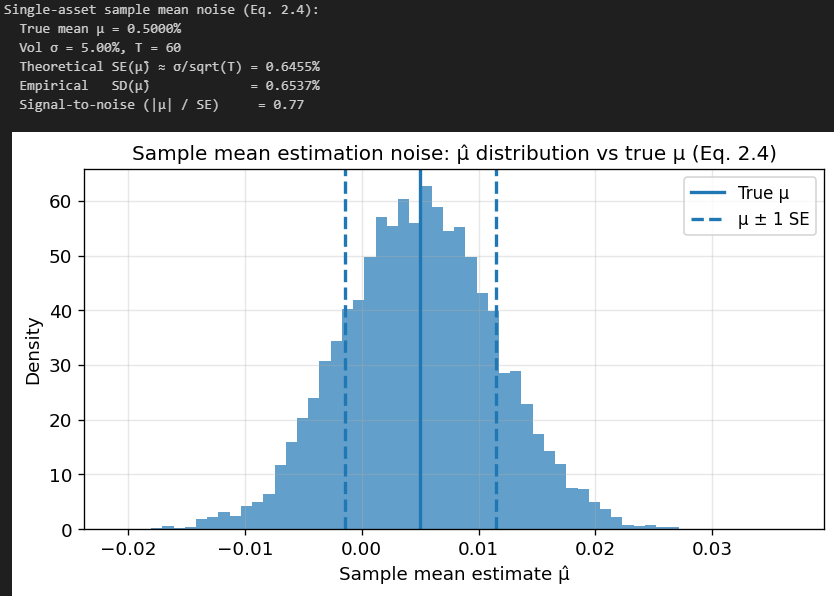

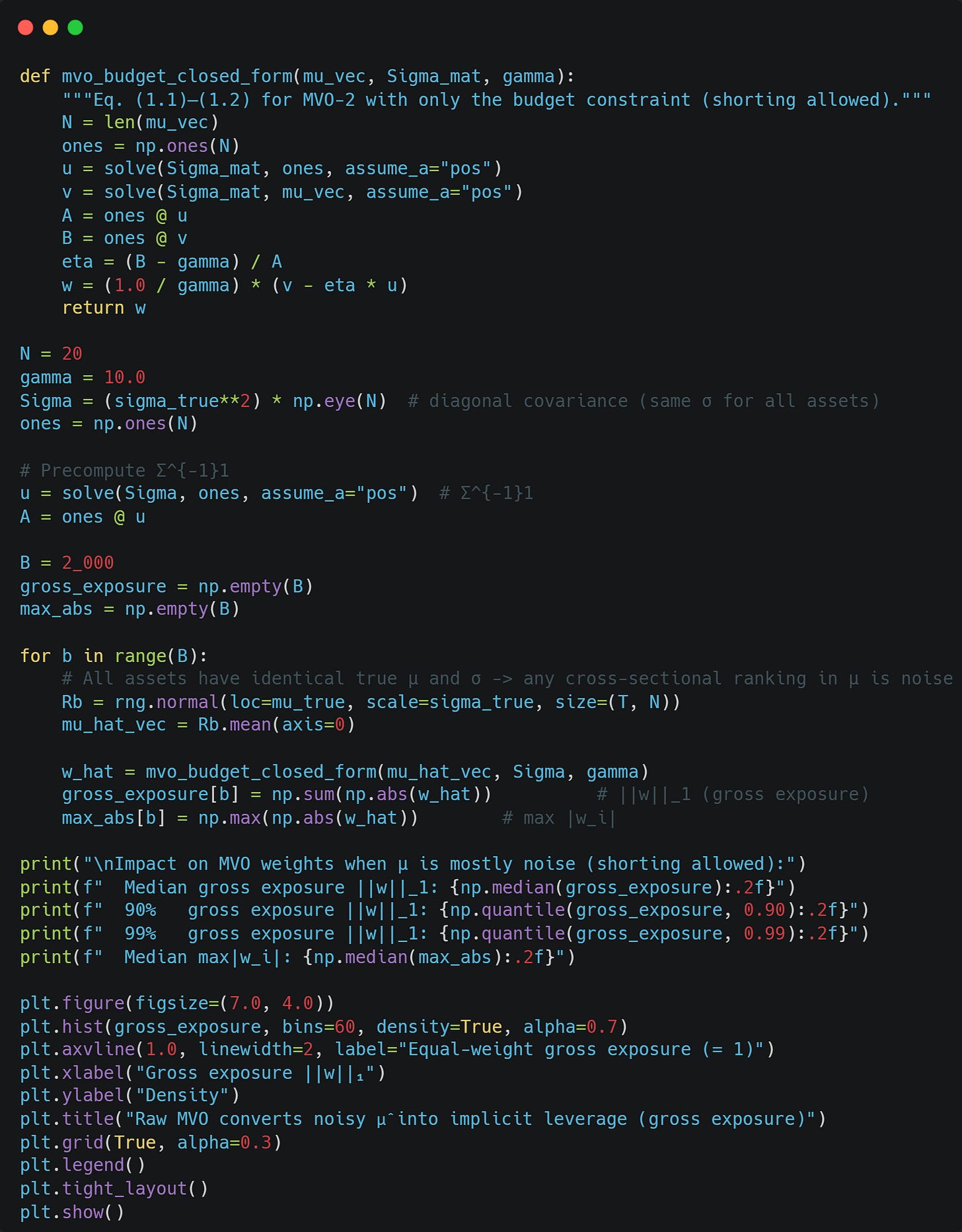

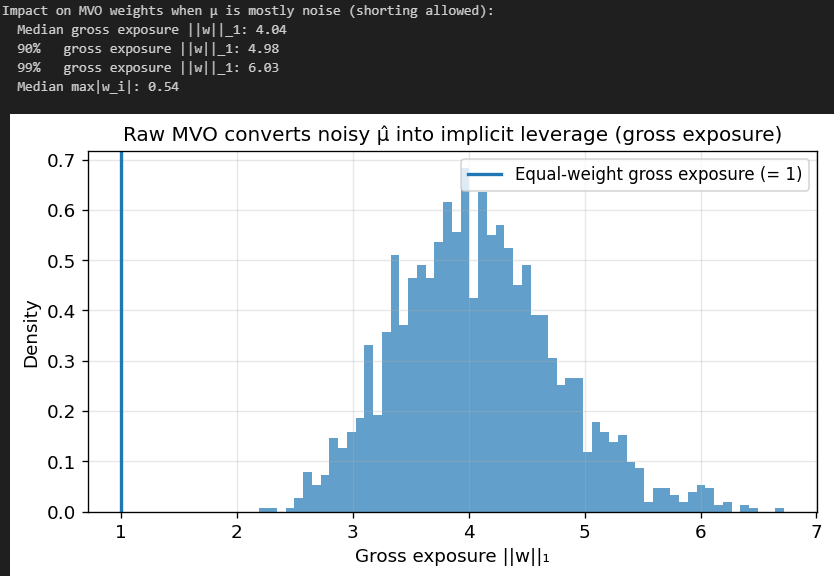

And now the impact on our portfolio weights from MVO. We assume 20 assets with identical true means, so any variation in mu is pure noise.

Our gross exposure is through the roof! A typical MVO portfolio here is equivalent to 200% long and 200% short, 4x leverage. Our right tail on Gross Exposure is also huge, so the portfolio sometimes ends up being 6x levered. The largest single position is also 54% of the portfolio, even though we have 20 assets.

This shows just how much of an extreme impact estimation noise in mu has on MVO.

Why covariance estimation becomes dangerous when inverted

The second failure mode is subtler: even if covariance estimates are “more stable” than mean estimates, the optimizer requires hat{Sigma}^{-1}. Inversion is the mathematical operation that turns moderate estimation noise into potentially huge weight noise.

To see why, consider the eigen-decomposition of the true covariance matrix:

where Q is orthonormal and

with lambda_i > 0$ if Sigma is positive definite. Then

Small eigenvalues become large eigenvalues after inversion. In portfolio terms, eigenvectors associated with small variance directions are precisely the directions the optimizer finds attractive: they offer “cheap risk.” But in finite samples, the smallest eigenvalues of hat{Sigma} are often dominated by noise (especially when T is not much larger than N). When the optimizer leans on these noisy low-variance directions, it produces extreme, unstable weights.

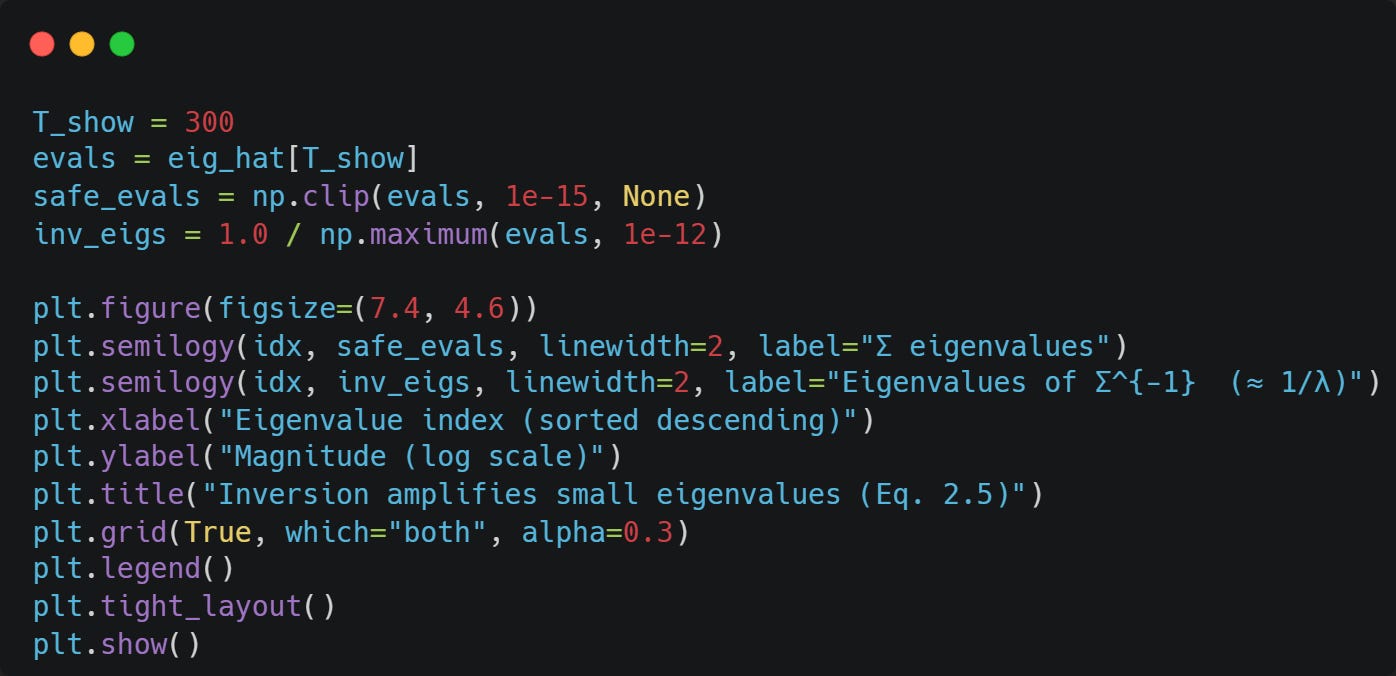

This is not hypothetical. A basic dimensionality fact already creates a hard boundary: if T < N, the sample covariance hat{Sigma} is singular (rank at most T-1), so hat{Sigma}^{-1} does not exist. Even if T is only moderately larger than N, hat{Sigma} can be ill-conditioned, making numerical inversion unstable and conceptually unreliable.

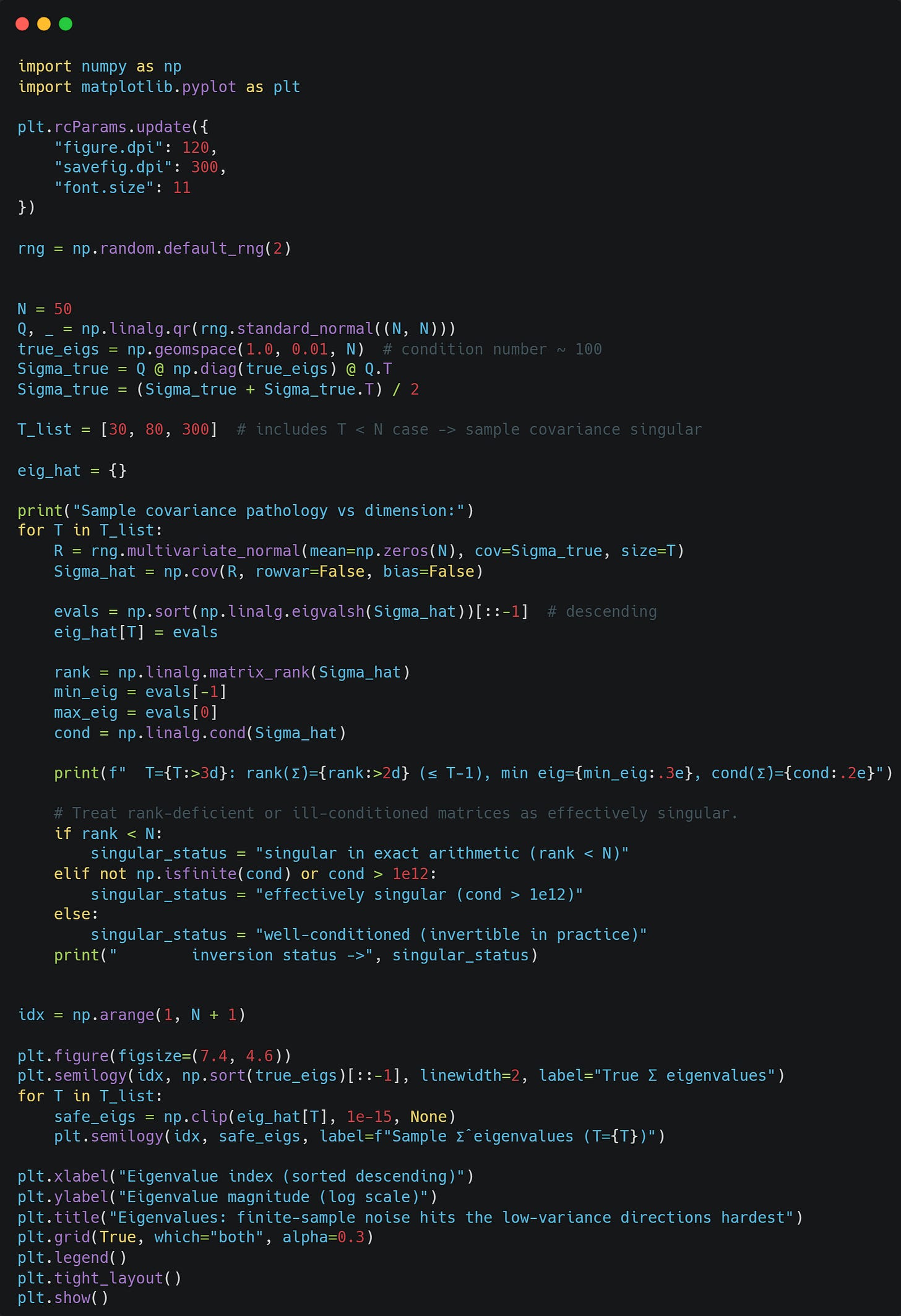

Let’s consider three cases: T < N, T ≈ N, and T > N, and look at the impact that T has on the estimated eigenvalues:

You can clearly see one thing: For the estimates where T = 30, Sigma becomes singular, and the 30th and further smallest eigenvalues just become 0. For T = 80, we can still see that the smaller eigenvalues are systematically underestimated. The estimates become better as we increase T to 300.

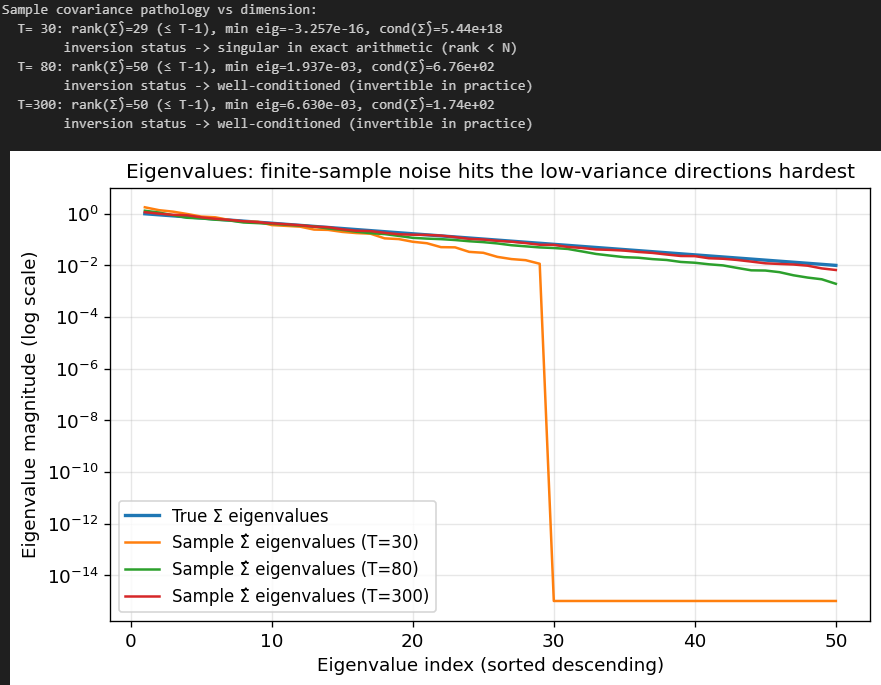

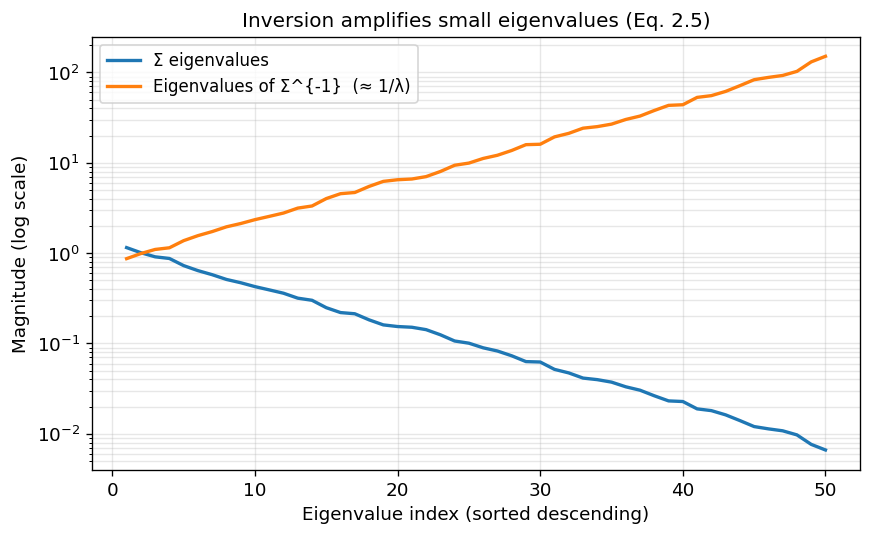

Now, let’s look at estiamted eigenvalues of Sigma and Sigma^{-1} for T=300:

The smaller the estimated eigenvalues, the larger the estimated eigenvalues of the inverse of Sigma.

Note: The y-axis is logarithmic on both plots, so linear → exponential!

Sensitivity Analysis: How estimation errors translate into weight errors

A useful way to formalize “error maximization” is to compute how small perturbations in mu and Sigma affect the optimizer.

Consider the unconstrained (besides budget) mean–variance utility maximization (MVO-2). The population optimum satisfies

with eta^\star chosen to enforce 1^T w^\star = 1. The plug-in estimate is

Write estimation errors as

A first-order expansion (informally, a matrix Taylor approximation) uses

A first-order perturbation of the optimizer gives

The last term enforces the budget constraint (with delta eta the perturbation in the multiplier); dropping it isolates the two main channels.

Several qualitative conclusions drop out of (2.8):

1. Mean error passes through Sigma^{-1}. Even if delta mu is moderate, multiplying by Sigma^{-1} can produce large changes in w, especially in directions corresponding to small eigenvalues of Sigma (or hat{Sigma}).

2. Covariance error enters as a “sandwich” with Sigma^{-1}. The term Sigma^{-1} * delta Sigma, w^\star has Sigma^{-1} on the left; if w^\star already has large exposures along unstable directions, covariance errors further distort them.

3. Budget adjustment can amplify instability. The multiplier eta is computed using 1^T Sigma^{-1} mu and 1^T \Sigma^{-1} 1$. If either of these scalars is unstable due to \Sigma^{-1}, the adjustment needed to enforce 1^T w=1 can itself swing drastically.

The key is not that delta mu and delta Sigma exist—of course they do—but that MVO transforms them with Sigma^{-1}, a potentially high-gain operator.

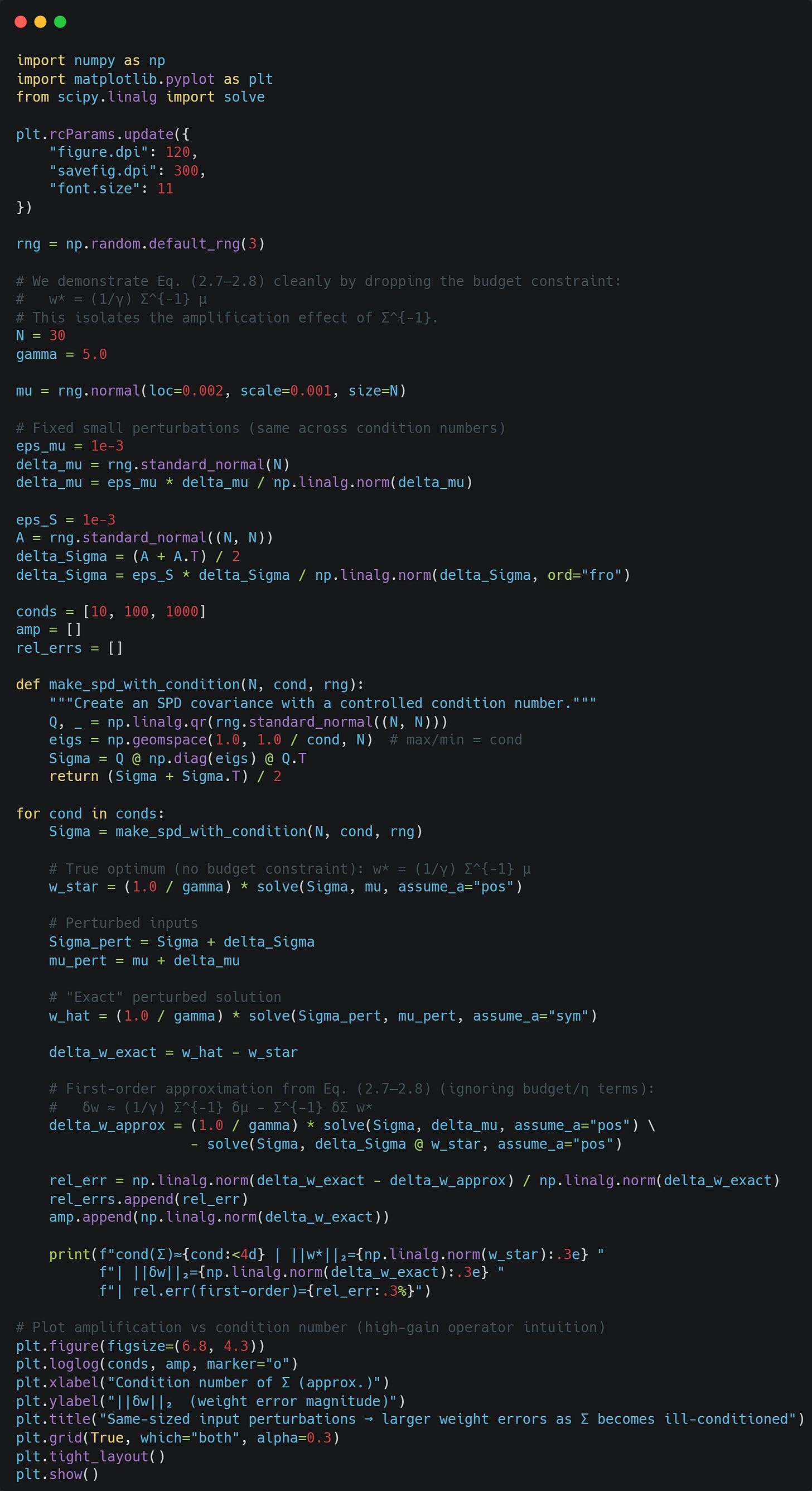

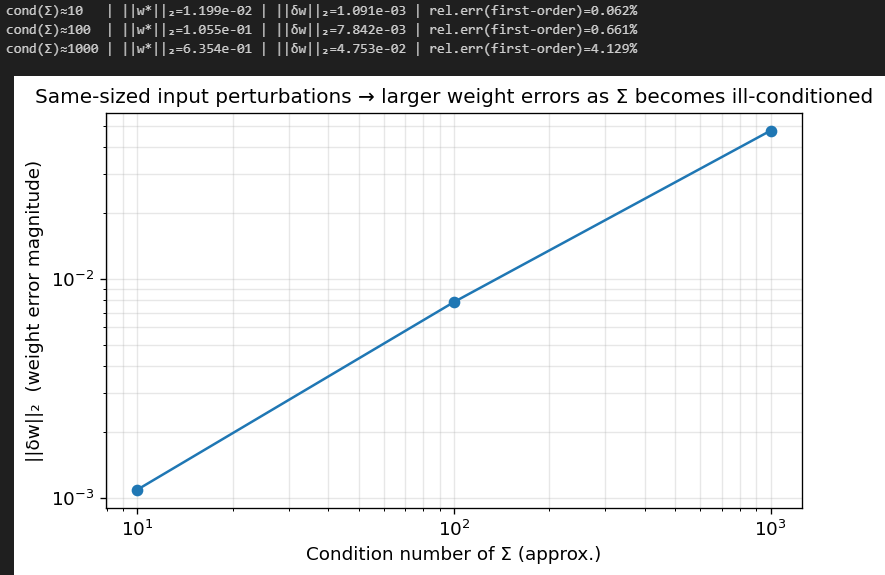

Let’s see how a badly conditioned Sigma affects delta w. We’ll drop the budget constraint so eta doesn’t influence the analysis:

You can see clearly that as Sigma becomes ill-conditioned, the error in w grows.

Optimizer’s curse

Another lens is the optimizer’s curse, a general phenomenon in statistical decision-making: if you choose the argmax of a noisy objective, the achieved value is biased upward in-sample, and the chosen decision is biased toward noise.

Formally, because hat{w} maximizes hat{U}(w),

but what matters is U(hat{w}). The difference

is typically positive and can be large in high dimensions. Intuitively, among many portfolios, some will look exceptionally good in-sample purely due to noise in hat{mu} and hat{Sigma}. MVO systematically selects those portfolios and then “locks in” their noisy characteristics via extreme weights.

This selection effect is strongest when:

The number of assets N is large relative to the sample size T

Expected return estimates are weak (low signal-to-noise);

Shorting/leverage is permitted (large feasible set);

Constraints are loose (optimizer can chase small estimated edges);

The covariance matrix has near-collinear assets (ill-conditioning).

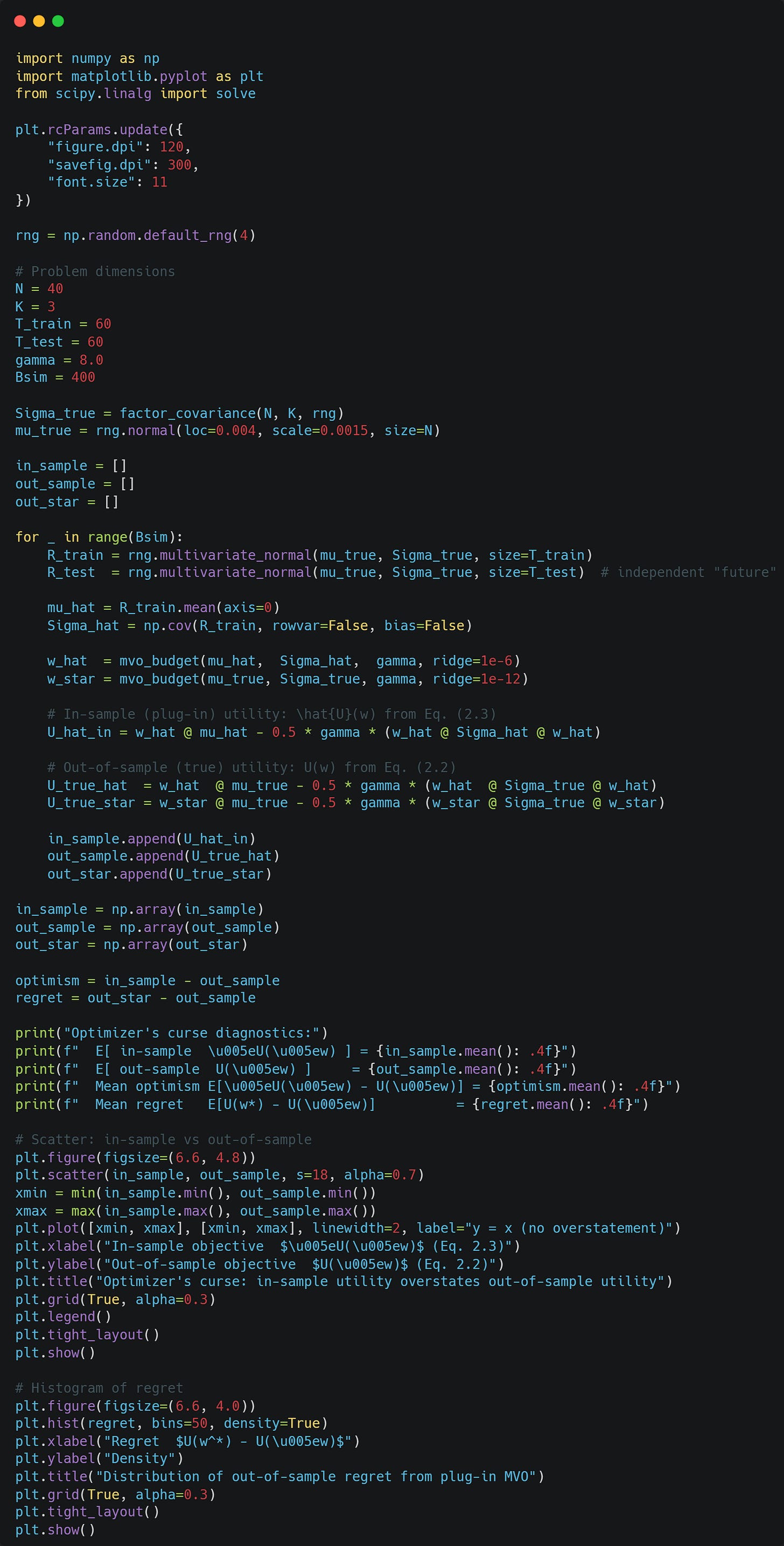

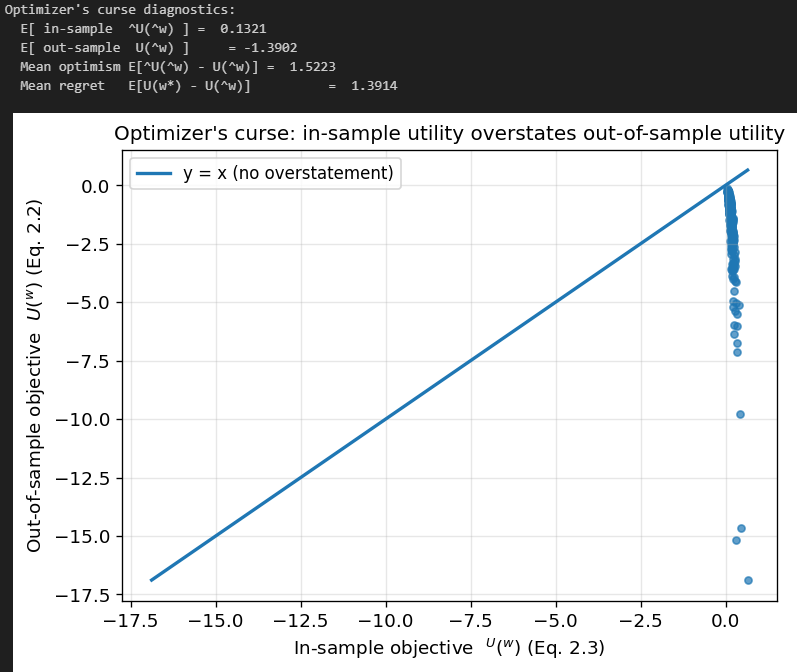

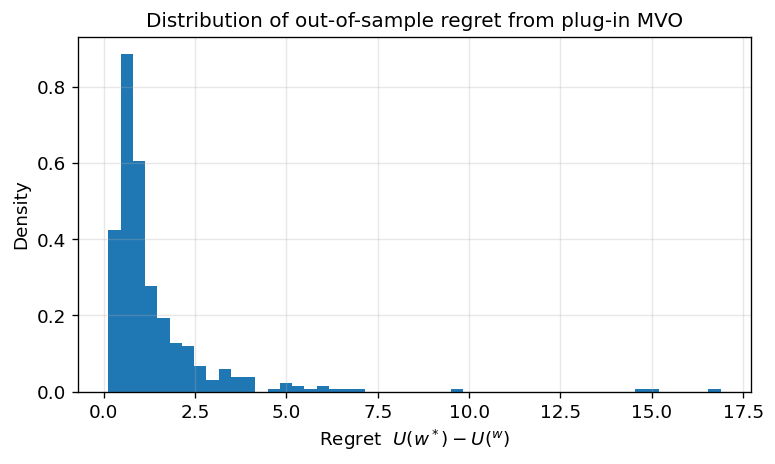

Let’s demonstrate the optimizer’s curse via Monte-Carlo.

You can see that even in an environment with equal true in- and out-of-sample mu and Sigma, due to estimation error, we vastly overestimate our utility in the in-sample.

Practical Symptoms: Instability, extreme positions, turnover, and disappointment

When raw MVO meets real data, the mathematical mechanisms above manifest in operational ways:

Extreme weights and implicit leverage. Even with the budget constraint 1^T w = 1, weights can be large positive and large negative (if shorting is allowed), producing large gross exposure |w|_1. Even with no-short constraints, solutions often sit on corners of the feasible region (many weights at bounds), because linear return objectives push to extremes.

High sensitivity to small input changes. Updating the estimation window by one month can materially change hat{mu} and hat{Sigma}, leading to large changes in hat{w}. This is not merely “rebalancing”; it is model instability.

High turnover and transaction cost drag. If weights change drastically, realized performance is dominated by trading costs and market impact, neither of which exists in the clean Markowitz formulation unless explicitly modeled.

Out-of-sample underperformance relative to naive allocations. A simple equal-weight or risk-parity portfolio can outperform a naive MVO portfolio after costs, not because those heuristics are theoretically superior, but because they are robust to estimation error.

These observations motivate the central practical conclusion: raw plug-in MVO is a high-variance estimator of portfolio weights. In modern terms, it is an overfit model.

The Spectrum of Solutions

This concludes the theoretical foundation.

The remaining 40 pages implement and test 11 robust portfolio construction techniques.

Each technique includes: Mathematical derivation → Clean implementation → Parameter tuning → Comparative results

Plus: Full research notebook (1250+ lines) with production-ready code. If you've made it this far through the theory, the implementations are where it pays off.